Science and humanities are often segregated in education and professional development. Even as a personal interest, the two disciplines are usually considered incompatible. In reality, they are complementary. Imagine if all science degrees included core humanities subjects in the first year? How would scientists, and science, benefit from a basic humanities perspective? This series looks for answers in some of the most common humanities disciplines.

How can literature benefit science?

Science needs to be written. It’s not science if it’s not shared, critiqued and built on over time. Science communication applies to everything from journal articles to popular science blogs. Ambiguous wording, too much jargon, or bad writing can turn off editors, reviewers and readers. Sadly, developing writing skills is not always a priority in modern science degrees. Graduates are being betrayed when they are packed off into the world of scientific research without a good command of written expression.

Including Literature subjects in science degrees is a good way to address this. Much of the ‘how to write’ advice that scientists can find online is not really useful if they don’t have a context to weigh it against. Top 10 lists of writing tips and ‘A vs B’ arguments are limiting, not enlightening. They teach a ‘one size fits all’ approach to communication. But effective communication is all about contexts and variable relationships, so teaching scientists how to identify, and work with, contexts is much more useful. Teach a man to fish…, as the saying goes.

Narrative nuances

Different styles of language apply to different narratives. The language conventions of a poem are different to those of a technical manual. No one can stop you from writing a poem in the style of a manual. But, if you do that, your audience will instantly change and the impact of your message may be lost.

There are three general stables of storytelling genres – fact, fiction and hard-sell. The main difference between fact and fiction narratives is the ‘accuracy’ of the content, although there can be some overlap (e.g. historical fiction). Beyond that basic classification, there are myriad styles, languages, and techniques used to present the context of the message, and gently open the reader’s mind to the author’s ideas. Science can easily be translated through many styles within either category, from science fiction to peer-reviewed poems.

But hard-sell is in a world of its own. Hard-sell is marketing, PR and business evangelism. This kind of story works by pushing the audience to support a product, service or idea, sometimes based on a fraction of the truth. Hard-sell narratives are loud; they don’t leave room for other perspectives, shades of grey, or inconvenient truths. Science is classier than that.

So, while hard-sell writing advice (similar to this Top 10 post by a business strategist, which recently got a lot of attention on social media among scientists) is great for pushing your latest brand, it’s not the best approach for communicating science. Science is unbiased, fact-driven communication…but that doesn’t mean the facts can’t be balanced by beautiful, persuasive prose!

Writing starts with reading

Studying literature opens the mind to language contexts. Beyond the black-and-white rules of spelling, punctuation and verb conjugations, grammar is highly contextual. Do I use ‘which’ or ‘that’? Should I say ‘him and me’ or ‘he and I’? ‘Predominant’ or ‘predominate’? Just like statistical analyses, neither option is wrong in itself…it becomes ‘wrong’ when used inappropriately. And just like statistics, the easiest way to learn these contexts is by reading literature.

The active vs passive voice debate is a classic example. Active voice is Journalism 101, the standard for mass media communication styles, e.g. news stories, marketing material and corporate press releases. It’s immediate and attention-grabbing. When used effectively, it’s a great hard-sell technique. Active voice encourages action and acceptance.

Few arguments for using the active voice in science point out that passive and active are just two different types of language context, each with their own relevant usage. The main error that pro-‘active voice’ arguments make is claiming that passive is outdated and has no place in science. This is not true. In fact, as Simon Leather argues eloquently in this piece, the active voice simply ‘encourages carelessness, partisanship and…does no favours to the English language or science.’ In contrast, writing in the passive voice creates prose with discipline, precision and an unbiased viewpoint. It encourages thought and questioning. Isn’t that what science is all about?

Peer-reviewed literature

Scholarly journals didn’t invent peer review. Literature (of the literary kind) has undergone a similar qualitative process for centuries. How do we know that Jane Eyre is ‘better’ (and a thousand times more romantic, in my opinion!) than 50 Shades of Grey? Or that The Ancient Mariner is not in the least bit comparable to Little Miss Muffett?

Quality literature is timeless. Its impact and messages last long after its contemporary trend fades. Why? Because its narrative engages many people, across many walks of life. It has application and relevance far beyond a niche audience.

History of science

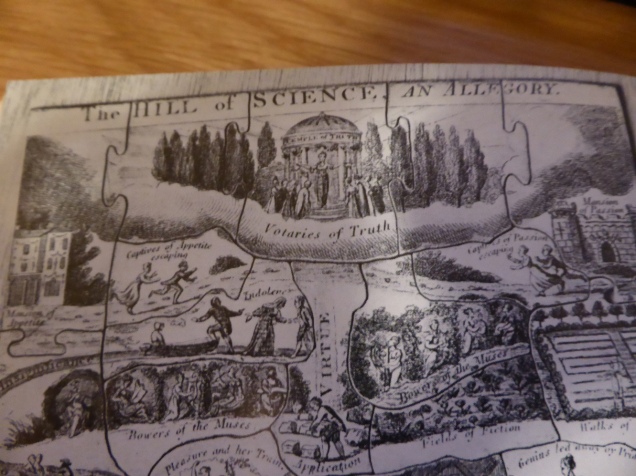

Studying literature also gives modern science a context. From the works of Aristotle and other classical scientists, to Chaucer’s (1343-1400) astronomical lore, and Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s (1743-1825) dream sequence, The Hill of Science, we learn that the struggle between science and society is not a new development.

Matthew Arnold (1822-1888), a much-misunderstood Victorian poet, wrote (Literature and Science, 1882): “…we shall find that the art and poetry and eloquence of men who lived…long ago, who had the most limited natural knowledge…have in fact [a power] capable of…helping us to relate the results of modern science to our need for conduct, our need for beauty.”

Whether or not we agree with the sentiments we read in these texts, understanding contemporary views of science over time can help us deal with the science communication obstacles we face today (more on this in a future post).

Empathy and intuition

Not the most popular words in scientific circles. However, these critical human qualities are increasingly overlooked as we get more and more complacent about technology filling in the gaps for us. A recent study showed how reading literary fiction, compared to popular fiction, non-fiction or nothing, improved the capacity for empathy. This is not surprising. Literary fiction is real and engaging. You need to pay attention to follow the story and understand each character’s development. Sometimes you have to fill in the gaps yourself based on your gut feeling.

Long ago, Aristotle wrote (Nicomachean Ethics, 1.7): “Wisdom must be intuitive reason combined with [scientific] knowledge.” It might sound strange, but empathy and intuition are really useful in scientific research. Intuition and creative thinking balance the logic and reason of scientific thinking, allowing a more realistic perspective of study systems. The ‘hard’ questions about humanity are the often the ones that can be most useful to solving sustainability problems, particularly in studies of ecosystems that are intricately linked to human communities (e.g. urban or agricultural landscapes). Read Joern Fischer’s nice summary on how intuition can benefit science here.

What do you think? Can studying Literature benefit science disciplines, or is it a waste of time?

© Manu Saunders 2015

You’ve mischaracterized my advice about writing. It’s the opposite of “hard-sell.” It’s about telling the truth.

LikeLike

Thanks Josh, that’s true, you clarified that in your post. I wasn’t referring to the accuracy of the material, but the style in which it is delivered. The point I am making here is that not all your advice is applicable to scientific writing, especially in my field of ecological sciences. But your advice is great for business or media communications contexts – if I had read it when I worked in corporate comms many years ago, I would have nodded along happily while reading! 🙂

LikeLike

Interesting article Manu. I’m a firm believer that there is not and should not be a division between the sciences and humanities, and don’t think students should be encouraged to see them as separate or choose between them at an early stage in their education. People working in or involved in the humanities can benefit from having science skills and knowledge, just as people working in science can benefit from learning skills in creative and persuasive writing. Think about Björk’s amazing project Biophilia, which involves scientists and engineers as well as musicians and singers.

I did want to comment on your observation that sciences teach rules and principles, while humanities teach context, as I think that this division could also be challenged. In particular, philosophy is about rules and principles, though these are developed and contested rather differently than in the various sciences. And philosophical logic is thoroughly rule-based….

LikeLike

Thanks Emma, great point. I agree, philosophy (& many other humanities) engages with rules and principles, but aren’t these usually relevant to contexts? Identifying the ‘rule’ in a system or object requires a certain amount of deeper thought to also understand what is going on around the focal object (sometimes this understanding is conscious, sometimes not) – meaning can’t be separated from the system/users etc. Perhaps saying that science teaches ’cause & effect’ is better wording (and again, I’m talking about common degree structures in this series, not science as a whole!).

LikeLike

Great, though-provoking post! I’d have to disagree with you (and Simon) on the active vs. passive voice, though – passive has certain particular functions at which it’s very good, but in general, I think it steals away our opportunity to write directly, engagingly, and honestly. But your larger point is bang on: to understand the advantages and disadvantages of active voice (or anything else), you really have to have read broadly and thought deliberately about what you’ve read and what you’re trying to write. Lists of rules are confining and, in the end, not that helpful.

LikeLike

As a humanities scholar I’d agree that the two are intimately linked. I’m not sure about the view that sees the humanities as simply informing ways of writing about and sharing science’s breakthroughs though (not that this is your argument here). Work in the humanities has moved a long way beyond a sender-message-receiver way of understanding communication but unfortunately this understanding of communication seems to inform some perspectives on science communication.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s brilliant that you’re thinking it through btw. Great stuff.

LikeLike

Thanks! I completely agree, humanities have much more to offer than just writing/comms skills – all to come in the rest of the series! 🙂

LikeLike

Studying literature might make for useful diversions for scientists, I have no doubt that knowledge of literature and humanities has nothing of value to add to science. And I say that as a person who has bachelors and masters degrees in physics.

Have you ever seen a scientific paper? The language it is written in might be English, but to most English speakers the paper might as well be in Martian. Papers are full of equations, and mathematical formulae and models. When a scientist reads a paper, the stars of the paper are not the English words, but those equations and formulae.

No amount of literature will change the way a 6th order multi-dimensional partial differential equation will be written and solved. No matter how you massage the English words, make them more ‘literary’, the paper will remain meaningless unless you also understand the mathematics and science that form the basis of the paper.

Knowledge of humanities will not help (and really has rarely helped) further science, baring maybe a few exceptions here and there and even that is debatable.

Science and humanities are two orthogonal fields of learning. Maybe humanists can say that knowledge of science can help the humanities, not many scientists will agree that that the reverse is true as well.

Unfortunately, your entire premise here shows how little you understand about scientific writing itself. I do not know your background, but it appears to be non-technical, at least non-mathematical.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. I don’t believe that science & humanities are orthogonal, they are complementary. This post is one of a series – you can find the rest of the series via the link at the top of the page. As a whole, the series argues that humanities education can help broaden the context of a science degree to enhance the way a scientist approaches research as a whole, not just writing. This is not a new argument, as there is already evidence showing the benefits scientists can gain from studying humanities.

I am familiar with scientific writing, and I believe successful communication does not depend on the complexity of concepts themselves, but the way they are explained to readers – a good communicator can make an uninitiated reader understand the most difficult concepts.

LikeLike

Thanks for the response Manu. Let me address your second point first. If you are writing science for the masses (and I believe that kind of science writing is every bit as important as technical papers), like Neil DeGrasse Tyson, or Carl Sagan, then yes you need to be an eloquent writer, with suitable skills to grab and keep the readers attention. On the other hand if you are writing a technical paper, language is not anywhere near as important.

There is a a reason why a technical paper written in English is still understandable to someone in the same field, whose knowledge of English might be rudimentary at best. It’s the mathematics, the notation and nomenclature, the logic, and rules of the science that speak to the reader. A lot of these papers are quite bare on words, leaving the mathematics to do the talking. No judgements are given, as that is a strict no! Readers are left to form their own judgement on the merits of the arguments presented. Conclusions are presented and defended.

And mathematics is certainly not governed or influenced by literature or humanities in any way at all. Can you give one example of literature influencing mathematical notation or development? In fact florid or artistic language is discouraged. Scientific papers are meant to be pithy and to the point. You will see phrases like “applying equation x to proposition y, leads to rule z, and a modification of theorem abc….” What you won’t see is something like, “equation k is a lovely modification of equation m, which when married to proposition u produced the aesthetically and artistically pleasing new proposition f, which as you can see is mathematical perfection.” There is no role for literature-like writing in this world. This is a world of cold facts and hard evidence, such a world has no place for artistic color or poetic license.

Now on to your second point, I take strong issue with your assertion that “there is already evidence showing the benefits scientists can gain from studying humanities.” What evidence? Can you name any Nobel Prize winners who have said that their discoveries were prompted by, or inspired by their knowledge of humanities? The argument that humanities “broadens” a scientific education has been made since time immemorial, almost exclusively by humanists. Rarely have you heard a scientist of any note stating that knowing Shakespeare, or Modigliani etc will result in better science.

Scientists enjoy humanist pursuits. But rarely do they attribute their scientific successes to humanities. The Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman liked playing the bongo drums, and charcoal sketching, but only as diversions. Also he picked up those activities quite late in his career, after he had done a lot of his groundbreaking physics work. Almost all great scientists are humanistcally inclined, but that’s it. None, or very few have ever thanked William Shakespeare or Picasso for being inspirations or guides for scientific excellence.

Also, history is not on your side. Brilliant scientists and engineers have since the invention of fire done their work without needing humanistic guidance or broadening. There are always one off examples of scientists and engineers using art as a guide, but in the grand scheme of the inventiveness and discovery, such examples are minuscule tiny fraction. Nikola Tesla was thinking of Goethes writing walking home one evening, when he solved the problem concerning his invention of the electric generator, perhaps one great (and at best questionable) example of literature inspiring a solution to a complex problem, but hardly enough to make a general sweeping conclusion about the value of humanities to science. What about the millions of other little or equally important inventions that were done by scientists and engineers tinkering in their labs, painstakingly collecting data, carrying out experiments, without the need to think of Goethe or Shakespeare? And who is to say that Tesla would not have solved the problem eventually as he did for so many other inventions?

When the National Cancer Institute created its cancer expert group, it brought together geneticists, physicists, chemists, mathematicians, biologists, electrical engineers, chemical engineers, and other engineers too. Basically a group of scientifically literate people who were not necessarily trained cancer researchers. But this group has done amazing work in discovering cancer pathways and other discoveries. Could an artist, or poet, or sculptor have added any value to such a group?

I am not saying that the study of humanities is not worth pursuing, and people who are so inclined, should do so. But I am not at all sold on the fact, that humanities are needed to produce great science.

Finally, exactly what kind of thinking do humanities require that are not part and parcel of a scientific education?

LikeLike

Thanks for the additional comments, here & and on my earlier post. I disagree that “language is not anywhere near as important” in technical/scientific writing. It is vitally important. Language is the only tool available to us to communicate concepts & results. And what is the point of doing scientific research if one does not communicate the results? Saying that language is not important to writing a technical paper, is like saying that statistical analysis is not important to presenting results. Statistics is a language too – knowing which analysis tools to use for your data is essential to presenting accurate results. Similarly, knowing the right language tools to communicate those results is essential to communicating those results. The advancement of science depends on the sharing of knowledge and concepts between disciplines and sub-disciplines. Disciplinary silos, which are based on a small group of people speaking the same dialect that is unintelligible to those outside the group, impede this progress. If a scientist wants their paper to be understood by scientists outside their peer circle, which will enhance citation rates and impact beyond their own discipline, they need to ensure it is written well. ‘Good’ writing means sentences written with correct grammar and syntax, regardless of the content.

I am not arguing that scientists should use ‘florid and artistic’ language in their papers. Humanities courses do not just teach ‘art, poetry & sculpture’; they teach grammar, syntax, critical thinking and human context – all of which are absolutely essential to designing, implementing and communicating good science.

LikeLike

Hi Manu,

the problem in today’s highly technical world is the extreme level of specialization. A marine biologist and a quantum physicist inhabit different worlds. The marine biologist will never understand a quantum physics paper, no matter how well the paper is written. And of course the vice versa is also true.

The quantum physicist and marine biologist are trained differently, have different tools and different nomenclature and notation, different first principles, different underlying laws and mathematical tools. It doesnt matter how well written your paper might if the reader does not have a solid understanding of all these basic facets of the science , they will just not be able to make sense of it. That is a fact (you might say unfortunate fact) of this era of specialization.

Its because of this extreme specialization that whenever some very complex multi-science problem (like a cure for cancer) is to be solved, multi-disciplinary science teams are created, so that each scientist can bring his unique knowledge and view to the problem. Where a geneticist might see an apparently unsolvable problem, the physicist or mathematician might be able to offer an immediate solution (as has actually happened), the geneticist did not have to learn anything more than the most rudimentary knowledge of the mathematics or physics, just enough to understand what the physicist might be saying. For their part the physicist and mathematicians just have to learn enough genetics to understand what the geneticist is saying.

The physicists, mathematicians, and geneticists do not need to read the scientific papers of each other works.

The second point you raise is about “critical” thinking. Humanists make the same argument about why their subjects are valuable to technologists. This something that I find to be a very weak argument. Critical thinking is absolutely fundamental to scientific education. Science progresses because scientists are always critically thinking about their subject and looking for improvements of solutions to unsolved problems. All the new inventions and discoveries happened because someone thought and looked at a problem critically. If a technical education did not equip its practitioners with superb critical thinking skills, all the science and technological progress made would have been impossible. I would go so far as to say that that a technical education is superior to a classical education in one major respect. Technical education marries critical thinking with problem solving. Unlike a classical education that apparently prides itself on teaching ‘critical’ thinking, whatever that might really be.

Scientific critical thinking and problem thinking are universal. They cross time, cultural and linguistic boundaries. From Thales of Ionia to Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Al-Hazen, Galileo, Huygens, Newton, Liebniz, Darwin,Wallace, Rayleigh, Roentgen, Einstein, Bohr, Born, Feynman, Tomonaga, Shimura, Noyce, Wiles, etc all speak different dialects of a common language that is unconstrained by time, location, and simple words. That is why their ideas and works are immortal. Their spoken language is immaterial.

As the great mathematician G.H. Hardy said, “Archimedes will be remembered when Aeschylus is forgotten, because languages die and mathematical ideas do not. ‘Immortality’ may be a silly word, but probably a mathematician has the best chance of whatever it may mean.”

I will close by stating that I have no problem with technologists enjoying humanities for any reason they like. But in my experience knowledge of humanities is absolutely unnecessary to the progress of science and technology. I believe that history supports me on this.

Thanks for a most interesting discussion on this subject. You are probably looking to move on to something else.

LikeLike

Sorry forgot to add one more thing. I did my education in the U.S., where the humanities form nearly 1/4 of the degree coursework. This includes:

1. Rhetoric and composition – 1 course

2. Masterworks of Literature – 1 course (choose from 1 of America, British or world literature)

3. Classic civilizations – 1 course (choose from a whole catalog of courses on Greek or Roman art/literature/politics/philosophy/history)

4. Foreign language (4 courses)

5. American history – 2 courses

6. American Govt – 2 courses

Personally, I am not not entirely convinced that the money spent on these courses was essential.

LikeLike