Recently, I’ve been hearing a recurring argument for why academic relocation is not a big deal compared to other jobs, usually in response to early career researchers discussing how often, and how far, they’ve had to move for work (e.g. this recent post over at Scientist Sees Squirrel).

Yes, the need to diversify one’s experience by moving locations is common to many careers. Most people will move once or twice, usually early on, to establish their future job or career path. Some careers demand continual relocation, even after establishment.

However, moving for academic careers is very different to most other mobile careers for one very important reason that is often glossed over: the mismatch between expectation and support.

Every academic should move at least once in their career. Staying at the same institution from undergraduate degree, through PhD, into postdoc and then lecturer position is risky, because it limits personal and professional development and reduces collaborative potential. This is especially important for people who follow academic career paths straight from high school. Academic research requires broad understanding of people, contexts and issues – this comes from diverse experiences working with different groups of people in different contexts. Moving institutions, especially as your knowledge and experience develops during the early stages of your career, provides huge benefits in broadening your mind and skills.

But…the expectation (not choice) of repeated relocation, without guarantee of a career progression, is not sustainable for most people. This is something that few other careers are characterised by.

Sure, there are plenty of other careers where moving is required for the job: police, teachers, military, bankers etc. The big difference between these careers and academia? They usually progress within a single organisation or government department. You already have a job, and your employer requires/gives you the option to move elsewhere. Hence, the move is often organised and subsidised by the employer. Military personnel, for example, have a whole internal department that help them pack and move house, find a new house at the new location, find new schools for children etc.

In contrast, if academics move location, they very rarely do it within the same university. This means that the burden of relocation costs and difficulties are covered personally by the academic and their family. Relocation assistance is often provided for senior-level or permanent academic positions, and some PhD scholarships also include limited reimbursement for moving costs.

But fixed-term postdoc contracts rarely include relocation costs. Yet this is the career stage that most academics are expected to ‘diversify via dispersal’, and the stage they most benefit from experiencing new contexts.

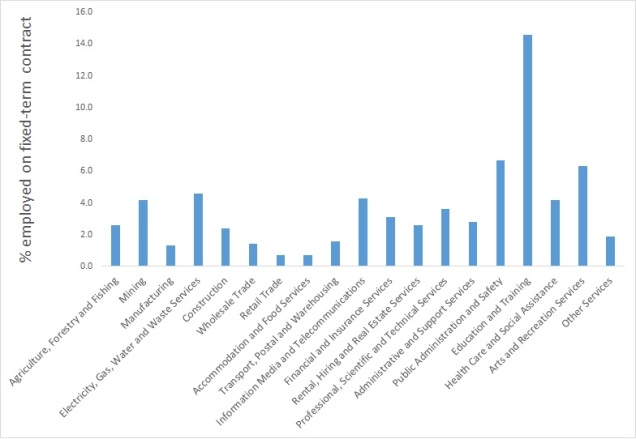

Unlike many other careers, relocation is typically the only option to pursue an academic career. In Australia, the Education & Training sector (including academia) has the highest percentage of people working on fixed-term contracts.

And it’s not like you can just find another suitable job in a similar organisation across town when your contract is done. Although, academics in large cities with more than one university have an advantage here – they have more chance of moving to new academic positions without having to move home, compared to academics in regional locations where universities are few and far between.

So no, academic nomadism isn’t just like every other career.

I don’t think it helps to push the notion that ‘constant relocation is normal, get used to it’. This attitude just perpetuates selection for a certain type of privilege…the financially-secure, the unattached, the able-bodied…people who have the will and ability to keep moving.

Cost of living is a lot higher today than in my parents’ day; moving town is now a significantly bigger financial and personal commitment than it was, say, 30-40 years ago. Even 20 years ago, when I first left home, it was a different story. Let alone moving overseas. Throw partners and children into the mix, and it all gets a bit too much for a lot of people.

As I said at the top, I think it’s critical that academics move at least once, especially at the early stages of their career. Most people can handle the financial commitment of one or two big moves. But beyond that, we should be talking about solutions for managing the constant relocation problem, not justifying its existence.

© Manu Saunders 2018

Spot on. Though I think the underlying problem is casualisation and short term contracts in the sector. As you say, the sense that moving is necessary amplifies the difficulties for those trying to forge a career who have children or other caring responsibilities – people who just can’t easily pack up and shift.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Part of the problem is also the research…when you move often, you can’t establish a long term research project and the time it takes to adjust to a new area (especially wrt field research) slows down your progress enormously. Speaking from experience, doing a field experiment in a new country was a steep learning curve. Even without the field work it takes weeks or months to settle into a new place before you can really get your research going at a good pace again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Completely agree. Early career is the stage you need support to be establishing a lab, attracting funding etc….all while you’re moving around the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not to mention as a post doc you have to immediately start applying for new jobs after you get one haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very nice point! I’m facing this problem right now, even as a professor moving between tenured jobs. My relatives and friends who work in the corporate world always get financial and logistic help when moving.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am in partial disagreement. Not denying the special difficulties of moving that an academic career can cause, but here are some counter-facts about moving in the non-academic world.

1) Moves required and supported by the organization for which someone works and will continue to work are different from those resulting from other issues In corporate life, only those above a certain level are given financial and logistic help, and increasingly only a few are offered the opportunity to move to a new location when a company chooses to move a facility. Corporations do not move their support staff…they hire new at the new location.

2) Military personnel are constantly at risk of losing their position, as a result of failing to be selected by a promotion board or through Congressionally mandated reductions in force (e.g. after the Viet Nam war when I, like many others, was found to be no longer needed.) The process is much like not getting tenure by a certain time, and though there is a final move partially supported by the military, there is no help getting settled on the other end, and goods are not moved “anywhere” but within a small range. Those lower in rank or grade get less assistance (there was no help for me in finding an apartment in the Washington, D.C. area–I was on my own.)

3) One of my brothers-in-law, an engineer, suffered through a succession of moves enforced by one of the many companies he worked for losing a government contract, whereupon much of the workforce was fired at one time. His severance pay never covered the cost of the move (the house he had bought was now worth less, thanks to the loss of a major employer; the next house he had to buy was in a hotter market because there were jobs and people moving in) and he had no assistance in the move. This is a very common cause of enforced moves in the non-academic civilian population, and it is extremely expensive for the laid-off workers. Where that plant had been generating a substantial number of jobs, now there are unemployed people trying desperately to find something in their skillset. For the lower levels (lower paid, lower status, assumed lower level of skills) there is no help–they must move, and move quickly, if they want any chance at maintaining a standard of living even three steps below what they’ve had. If they don’t move, stuck in the wishful thinking that the mine will open again, the manufacturer will reopen the factory, they end up stuck in poverty as their town or city decays around them for lack of well-paying jobs. (People I know who’ve been laid off in such situations include those in multiple segments–information technology (including both software and hardware development), finance, aerospace, “energy” across a broad range, “public service,” biomedical, etc.)

4) Employers game the system in order to hire younger, less-skilled workers they can legitimately pay a lower wage, and find reasons to dump older workers who are earning more and who have more invested in the company’s pension plan (if any) or at least are drawing higher contributions to their retirement plans. Thus every corporate employee except in the nosebleed suites is at risk of termination (and extreme difficulty in finding another job) by age 50, and an unplanned “retirement” after 60 is almost inevitable in many fields. It’s happened to many of my friends. No golden parachutes (or even torn nylon ones) for them. And often they must move to find a job, since they will be called “overqualified” for jobs they’d be willing to take (but that barely support one person, let alone a family.) But they are given no help–they must figure out on their own how to find another job somewhere and be ready to yank up their family despite the difficulties.

The stresses felt by the individuals and the families are much the same, whatever the cause of the unanticipated need to move to new employment. Unless someone is at the top rank, nurtured by a the employer for his/her presumed value to the organization, a move costs money, time, and stress. And yes, the need to be mobile and move around does select for those who have a solid financial base already, whose personal responsibilities are small (one spouse, fewer than four children, no disabled persons in the family, etc., property easy to rent or sell upon leaving. This isn’t good, and it isn’t fair, but it’s not a burden on academics only.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comments. Yes, there is a huge range of experiences when it comes to moving for work. I had 10 years pursuing another career path before returning to uni to pursue academic research, so I am fully aware of the challenges involved in moving for jobs in the non-academic world. In this post, I am arguing that someone pursuing the traditional academic career path (phd, postdoc, professor) is restricted to the type of organisation they can work in, i.e. a university. Therefore, I’m comparing it to other non-academic jobs that are also similarly restricted to what type of organisation they can work in, eg police, state teachers, bankers, military officers etc. This is of course very different to jobs that perhaps have more potential of moving between types of organisations/roles in the same location vs moving location. And of course there are multiple shades of grey in this discussion, especially when comparing countries eg Australia vs USA.

LikeLike

In addition to the direct costs of moving (which are high!), you also have to deal with the possibility that your two positions will leave a gap in employment. It’s very difficult to coordinate the end of one position with the start of another. At current wages it is difficult to save money for even a month of unemployment. This is another way privilege interacts with academia. Not everyone has financial safety nets and can take the risk of unemployment between positions. I hope that we start to talk about solutions to these types of problems as part of the push for ‘diversity, equity and inclusion’ instead of just focusing on recruitment of ‘diverse candidates’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, completely agree

LikeLike

“This attitude just perpetuates selection for a certain type of privilege…the financially-secure, the unattached, the able-bodied”

Yes, having to move to a new city every couple of years has made it very difficult for me to manage some health problems that arose in the past few years! It takes a fair amount of effort to find good doctors in a place you have just moved to. These interruptions have definitely reduced my productivity, as they have prolonged the diagnosis period. In the US, the employment gap that Celia mentions (combined with universities doing a poor job of letting you know when your new health coverage will begin) can even lead to you being without health insurance for a time.

Another way in which moving for an academic career as an ECR is unlike other jobs is that often you are still doing research from the previous position, and in some cases have to start working on some things for the new job before you even start it, on top of arranging a move and trying to settle in to a new place.

LikeLiked by 1 person